|

Abstract The anterior accessory saphenous vein (AASV) is a common source of primary and recurrent lower extremity varicose veins. Reflux in the AASV can occur independently or simultaneously with great saphenous vein (GSV) reflux. A number of published reports describe recommendations and treatment of symptomatic refluxing AASVs, but descriptions of combined treatment are sparse. Treatment options for ablation of the AASV include both thermal and non-thermal techniques, and results are equivalent to ablation of the great and small saphenous veins. Although not commonly performed, concomitant ablation of the AASV and the GSV is effective and safe, and can be accomplished with minimal additional time. Concomitant treatment is an appropriate option that should be discussed with the patient. Keywords: Anterior accessory saphenous vein, great saphenous vein, ablation, combined treatment Disclosure:The author has no conflicts of interest to declare. Received: 07 July Accepted: 25 October 2021Published online: 07 July 2022 Citation: Vascular & Endovascular Review 2022;5:e01. DOI:https://doi.org/10.15420/ver.2021.07 Correspondence Details: Harold J Welch, The Vascular Care Group, 100 Camp St, Hyannis, MA 02601, US. E: hwelch@vascularcaregrp.com

Open Access:

This work is open access under the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License which allows users to copy, redistribute and make derivative works for non-commercial purposes, provided the original work is cited correctly.

|

Nomenclature and Anatomy

The anterior accessory saphenous vein (AASV) or, as it is formally known, the anterior accessory of the great saphenous vein, is a clinically important source of primary and recurrent varicose veins.1 The anatomy of the AASV was examined with ultrasound in a comprehensive paper by Cavezzi et al.2 Of course, there is significant variation in the venous anatomy of the lower limb, but the AASV typically lies within a fascial compartment and forms an ‘eye sign’ on ultrasound, similar to the great saphenous vein (GSV). It usually lies anterior and lateral to the GSV as it ascends the thigh. The terminus of the AASV is also variable, but most commonly it joins the GSV within 2 cm of the saphenofemoral junction (SFJ).2 The anterior thigh circumflex vein is a tributary of the AASV (although sometimes the GSV) and courses superomedial in the thigh.

The vein under discussion has several names and abbreviations. It has been called the anterior accessory GSV, the accessory saphenous vein and the AASV.3–5 This can lead to some confusion, and perhaps is one of the reasons why insurance companies often do not routinely cover treatment of this vein, given that it is seen by them as being only an ‘accessory’ to the GSV and therefore is downplayed as not important. One suggestion is to eliminate the ‘accessory’ designation, and name this the anterior saphenous vein. That designation is for the future and beyond the scope of this article. For the sake of consistency in this article, it will be referred to as the AASV.

Clinical Significance and Treatment

As known to venous practitioners, the AASV has important clinical implications. Due to anatomic variation the AASV can communicate with the GSV below the terminal valve, and if the terminal valve is incompetent, there can be direct reflux into the AASV. Additionally, the AASV can drain directly into the common femoral vein, which can also lead to reflux down the AASV.6,7

Schul et al. published a recent paper examining the importance of the AASV in clinical practice, using data from the American Vein and Lymphatic Society PRO Venous Registry.8 Patients in the study were divided into two groups: the primary group had no prior vein treatment, and the progressive group had a superficial venous intervention at some previous point. There were no demographic differences between the groups. The authors compared patients with reflux in the GSV and those with reflux in the AASV. They found that reflux in the AASV is common in patients with both primary and recurrent disease, has similar disease severity compared with GSV reflux, and has a higher incidence of superficial thrombophlebitis compared with the GSV.8 It therefore should be considered equivalent to the GSV and small saphenous vein (SSV) when considered for intervention and reimbursement.

Endovenous ablation, either by thermal techniques or ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy, of the AASV is generally not commonly performed. Treatment of the AASV ranges from 3.8% to 9.8% of truncal superficial veins ablated in several series.9,10

Theivacumar et al. examined endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) of the AASV in patients with isolated AASV reflux and a competent GSV and compared them with a group with EVLA of the GSV.3 They found that EVLA of the AASV would abolish SFJ reflux and had equivalent improvement according to Aberdeen varicose vein symptom severity score, and patient satisfaction when compared with EVLA of the GSV.3 Cavallini et al. published a report of nine incompetent AASVs treated with EVLA and found that the venous clinical severity score improved from a mean of 3.2 before intervention to a mean of 0 at 17 months.11

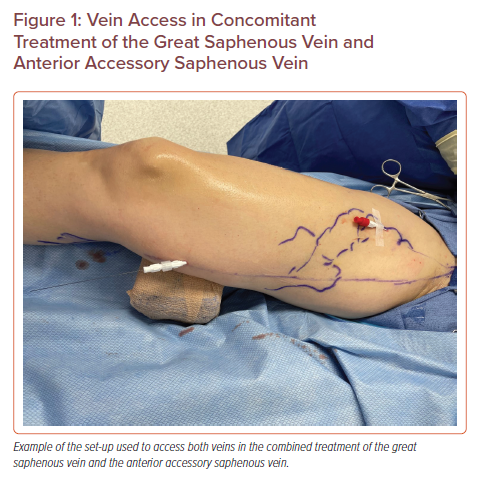

Vein Access in Concomitant Treatment of the Great Saphenous Vein and Anterior Accessory Saphenous Vein

One of the most common causes of recurrent varicose veins after GSV ablation or stripping is new reflux in the AASV. This was shown by Bush et al., with 24% of recurrent varicose vein patients having new AASV reflux, and O’Donnell et al., who showed that new AASV reflux was the cause of recurrent varicose veins in 19% of patients, second only to GSV recanalisation (32%).12,13

One explanation for this could be provided by an elegant study by Uhl et al.14 They dissected 400 limbs in 200 fresh cadavers and found lymph nodes between the GSV and the origin of the AASV, and identified dilated lymph node venous networks in approximately 15% of dissected cadavers.14 Another study investigated AASV reflux over time after radiofrequency ablation of incompetent GSVs and found that reflux in the AASV increased from 2% at baseline to 32% at 4 years.15

Baccellieri et al. examined the role of anatomy of the AASV at the SFJ and junctional reflux as a risk for recurrent varicose veins. Patients in group A had junctional (SFJ) and GSV reflux on ultrasound, while group B patients had only GSV reflux. After undergoing radiofrequency ablation of the GSV, a higher rate of recurrent varicose veins at 3 years was found in group A patients, and a direct confluence of the AASV at the SFJ was found to be a negative predictor for recurrent varicose veins.16 Attempting to mitigate such anatomic factors in recurrences after GSV endovenous ablation, Spinedi et al. published a report using a radial emitting laser fibre positioned at the SFJ, and had only one case of endovenous heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) class 2 (0.8%) and one EHIT class 3 (0.8%). Although no follow-up information concerning recurrence was obtained, they concluded that the procedure is feasible and safe.17

After thorough patient evaluation, including symptom and venous history, physical examination, and duplex ultrasound examination, if documentation of both GSV and AASV reflux has been identified, the decision to treat sequentially or concomitantly must be made. If treatment of both at the same time has been determined to be optimal for the patient, then one can proceed accordingly. Both veins are mapped with duplex ultrasound prior to prepping the leg.

The author proceeds with ablation of the GSV first. Given that the tumescent anaesthesia for the first vein ablation may compromise access to the second vein, it is suggested to gain access to both veins with a micro puncture kit and 4 Fr sheath, and instil the planned second vein sheath with injectable saline (Figure 1). After ablating the first vein (usually the GSV), attention is turned toward the second vein. Ablating the AASV after the GSV should add no more than 10 minutes to the procedure. Compression after the ablations should follow the recently published guidelines.18

Most published studies concerning ablation of the AASV describe sole treatment of the AASV, or group the results with ablation of the GSV and SSV. A case report of combined treatment has been published.19 The author’s experience with combined treatment of both GSV and AASV is similar to others, that is to say, not very extensive. Eleven patients were treated concomitantly with 1,470 nm laser (0.67% of ablations): five of those patients also had concomitant phlebectomy, one had phlebectomy at a later date, and five patients required no further treatment. The average length of the treated AASV was 12.7 cm (range, 7–26 cm), and there were no instances of EHIT or deep vein thrombosis in those patients.20

An interesting concept has been proposed to potentially treat a non-refluxing AASV concomitantly with ablation of a refluxing GSV in order to decrease the recurrent varicose veins that would arise from a future incompetent AASV.16,21 However, the 2020 appropriate use criteria state that ablation of AASV with no reflux, but GSV with reflux (CEAP classes 2–6) is rarely appropriate and ablation for a vein with no reflux is never appropriate.22

Reimbursement

As all vein practitioners know, the AASV can be the source of primary varicose veins in the setting of a normal, competent GSV. A number of health insurance payers in the US will not approve treatment of an AASV unless the GSV has been previously treated. This creates difficulties for the patient and practitioner when the GSV is normal, usually requiring repeated appeals for treatment.23

In the US, typical reimbursement for CPT code 36475 (laser ablation 1st vein) ranges from US$970 (£716; Medicare) to US$1,700–$2,500 (£1,256–£1,847) from private payers, and CPT code 36476 (laser additional vein) from approximately US$200 (£148; Medicare) to approximately US$500 (£369; private payers). Blue Shield of California insists that all refluxing truncal veins be treated in one session.24 Therefore, sometimes it is mandatory that combined treatment be performed.

Conclusion

The American Venous and Lymphatic Society published guidelines for the treatment of refluxing accessory saphenous veins in 2017. The recommendation was that symptomatic refluxing accessory saphenous veins be treated with thermal ablation or ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy to reduce symptomatology, with a recommendation grade of 1C. It also stated that further studies concerning the management of isolated accessory vein reflux are not necessary.25

The AASV is a common source of both primary and recurrent lower extremity varicose veins and has been shown to be clinically equivalent to the GSV in terms of symptoms and the relief of those symptoms after treatment. Combined treatment of the AASV and GSV is not often performed, but if concomitant reflux is identified in both the AASV and GSV on duplex ultrasound, the decision to perform staged or concomitant ablation of both truncal veins may be dictated by insurance companies, or warrants, at the very least, discussion between the provider and patient.

-

-

- Caggiati A, Bergan JJ, Gloviczki P, et al. Nomenclature of the veins of the lower limb: extensions, refinements, and clinical application. J Vasc Surg 2005;41:719–24.

Crossref| PubMed - Cavezzi A, Labropoulos N, Partsch H, et al. Duplex ultrasound investigation of the veins in chronic venous disease of the lower limbs: UIP consensus document. Part II. Anatomy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006;31:288–99.

Crossref| PubMed - Theivacumar NS, Darwood RJ, Gough MJ. Endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) of the anterior accessory great saphenous vein (AAGSV): abolition of the sapheno-femoral reflux with preservation of the great saphenous vein. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009;37:477–81.

Crossref| PubMed - Gibson K, Ferris B. Cyanoacrylate closure of incompetent great, small and accessory saphenous veins without the use of post-procedure compression: initial outcomes of a post-market evaluation of the VenaSeal System (the WAVES study). Vascular 2017;25:149–56.

Crossref| PubMed - Chaar CI, Hirsh SA, Cwenar MT, et al. Expanding the role of endovenous laser therapy: results in large diameter saphenous, small saphenous, and anterior accessory veins. Ann Vasc Surg 2011;25:656–61.

Crossref| PubMed - Muhlberger D, Morandini L, Brenner E. Venous valves and major superficial tributary veins near the saphenofemoral junction. J Vasc Surg 2009;49:1562–9.

Crossref| PubMed - Chun MH, Han SH, Chung JW, et al. Anatomical observation on draining patterns of saphenous tributaries in Korean adults. J Korean Med Sci 1992;7:25–33.

Crossref| PubMed - Schul MW, Vayuvegula S, Keaton TJ. The clinical relevance of anterior accessory great saphenous vein reflux. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2020;8:1014–20.

Crossref| PubMed - Ravi R, Trayler EA, Barrett DA, Diethrich EB. Endovenous thermal ablation of superficial venous insufficiency of the lower extremity: single-center experience with 3000 limbs treated in a 7-year period. J Endovasc Ther 2009;16:500–5.

Crossref| PubMed - Bradbury AS, Bate G, Pang K, et al. Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy is a safe and clinically effective treatment for superficial venous reflux. J Vasc Surg 2010;52:939–45.

Crossref| PubMed - Cavallini A, Marcer D, Ferrari Ruffino S. Endovenous treatment of incompetent anterior accessory saphenous veins with a 1540 nm diode laser. Int Angiol 2015;34:243–9.

PubMed - Bush RG, Bush P, Flanagan J, et al. Factors associated with recurrence of varicose veins after thermal ablation: results of the Recurrent Veins after Thermal Ablation Study. ScientificWorldJournal 2014;2014:505843.

Crossref| PubMed - O’Donnell TF, Balk EM, Dermody M, et al. Recurrence of varicose veins after endovenous ablation of the great saphenous vein in randomized trials. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2016;4:97–105.

Crossref| PubMed - Uhl JF, Lo Vuolo M, Labropoulos N. Anatomy of the lymph node venous networks of the groin and their investigation by ultrasonography. Phlebology 2016;31:334–43.

Crossref| PubMed - Proebstle T, Mohler T. A longitudinal single-center cohort study on the prevalence and risk of accessory saphenous vein reflux after radiofrequency segmental thermal ablation of great saphenous veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2105;3:265–9.

Crossref| PubMed - Baccellieri D, Ardita V, Carta N, et al. Anterior accessory saphenous vein confluence anatomy at the sapheno-femoral junction as risk factor for varicose veins recurrence after great saphenous vein radiofrequency thermal ablation. Int Angiol 2020;39:105–11.

Crossref| PubMed - Spinedi L, Stricker H, Keo HH, et al. Feasibility and safety of flush endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein up to the saphenofemoral junction. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2020;8:1006–13.

Crossref| PubMed - Lurie F, Lal BK, Antignani PL, et al. Compression therapy after invasive treatment of superficial veins of the lower extremities: clinical practice guidelines of the American Venous Forum, Society for Vascular Surgery, American College of Phlebology, Society for Vascular Medicine, and International Union of Phlebology. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2019;7:17–28.

Crossref| PubMed - Basgu HS, Bitargil M, Ozisik K. Isolated insufficiency of the anterior accessory saphenous vein: should it be treated alone? Cardiovascular Surgery and Interventions 2015;2:36–9.

PubMed - Welch HJ. Combined treatment of GSV and AAGSV. Presented at: 2022 Venous Symposium (Virtual). 15 April 2022. http://www.venous-symposium.com/virtual-program/.

- Muller L, Alm J. Feasibility and potential significance of prophylactic ablation of the major ascending tributaries in endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) of the great saphenous vein: a case series. PLoS ONE 2021;16:e0245275.

Crossref| PubMed - Masuda EM, Ozsvath K, Vossler J, et al. The 2020 appropriate use criteria for chronic lower extremity venous disease of the American Venous Forum, the Society for Vascular Surgery, the American Venous and Lymphatic Society, and the Society of Interventional Radiology. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2020;8:505–25.

Crossref| PubMed - Welch HJ, Schul MW, Monahan DL, Iafrati MD. Private payers’ varicose vein policies are inaccurate, disparate, and not evidence based, which mandates a proposal for a reasonable and responsible policy for the treatment of venous disease. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2021;9:820–32.

Crossref| PubMed - Blue Shield of California. Treatment of varicose veins/venous insufficiency. Policy Statement. https://www.blueshieldca.com/bsca/bsc/public/common/PortalComponents/provider/StreamDocumentServlet?fileName=PRV_TX_Varicose_Venous_Insufficiency.pdf (accessed 28 June 2021).

- Gibson K, Khilnani N, Schul M, Meissner M. American College of Phlebology guidelines: treatment of refluxing accessory saphenous veins. Phlebology 2017;32:448–52.

Crossref| PubMed

- Caggiati A, Bergan JJ, Gloviczki P, et al. Nomenclature of the veins of the lower limb: extensions, refinements, and clinical application. J Vasc Surg 2005;41:719–24.

-